IFP: Behind the Photos

This project collected IFP alumni photos to highlight the work of alumni promoting and advancing social justice worldwide. These photos were a testament to the commitment IFP alumni made to continuing social justice activities after their IFP Fellowship.

Explore IFP photo stories by month below:

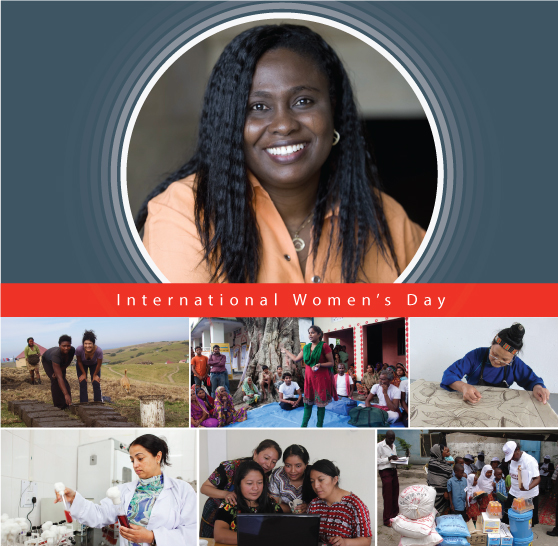

As part of its mission to provide higher education access to marginalized populations, IFP sought to address gender inequality by providing IFP Fellowships to nearly 2,150 women—50% of all IFP Fellows—from 22 countries worldwide. On this International Women’s Day, we would like to recognize IFP alumnae engaged in a wide range of endeavors and industries, working tirelessly to drive positive change for themselves and members of their communities.

We found in our IFP Global Alumni Survey (2015) that:

- 85% of alumnae felt that their IFP fellowship empowered them as a social justice leader.

- 72% of alumnae saw themselves as role models for members of their home community.

- 46% of alumnae created or helped create a new organization or new program, with 40% of these organizations related to gender issues.

Related issue brief: “Promoting Gender Equality”

On International Heritage Day, we interviewed Pedro Mateo Pedro, a native speaker of Q’anjob’al, a Mayan language of Guatemala, and an IFP alumnus from Guatemala. His work focuses on the documentation of the Mayan languages, especially Chuj, which is spoken in San Mateo Ixtatán in Huehuetenango. Mateo Pedro received his Ph.D. in linguistics at the University of Kansas in 2010 and completed a postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard University. Pedro is currently an Assistant Research Professor at the National Foreign Language Center, University of Maryland, and Executive Director of the Guatemala Field Station.

Can you describe the above photo? When and where was it taken?

This picture was taken either in 2011 or 2013 in San Mateo Ixtatán, Huehuetenango, Guatemala. I was working with two native speakers of Chuj, a Mayan language of Guatemala. The two speakers were my assistants in documenting how children were learning Chuj.

How does this photo link to your field of expertise?

This picture represents that kind of work that I do as a linguist, which consists in the documentation and revitalization of indigenous languages, in this case of Mayan languages.

Do you see a link between this photo and your experience with IFP?

With IFP’s support, I received my MA in Linguistics at the University of Kansas and started to work on the documentation of the acquisition of Q’anjob’al, my native language. Since then, I have been working on the documentation of the acquisition of Mayan languages.

Do you see a link between this photo and International Heritage Day?

I would relate International Heritage Day to language as a heritage, which people in the world have the right to speak and to be educated in their own language.

Are they any other comments you would like to share regarding the celebration of this day?

I would say that preserving linguistic knowledge is also preserving cultural knowledge. When a language is alive a culture is also alive.

Learn more about Pedro and his work here

Related publication: Leaders, Contexts, and Complexities: IFP Impacts in Latin America

Haldhar Mahto completed his IFP scholarship in 2005-06 at the University of London School of Economics and Political Science, obtaining a Master’s degree in NGO Management and Social Policy. Haldhar is currently a member of the Jharkhand State Food Commission, a state commission to ensure the efficient implementation of the National Food Security Act of 2013. The commission also provides policy inputs to the government of Jharkhand, India.

Can you describe this photo? When and where was it taken?

This picture was taken between the years 2007 to 2009 in a remote village Cheo located on the hilltops of the Sunderpadi block of Godda district in Jharkhand, India. The village and population are predominantly inhabited by the most deprived Tribal Community, known as Paharia They have been categorized as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG) and are among the eight protected tribal groups in the state. The PVTGs population is decreasing and is considered to be an extinct population. They are struggling to secure their minimum basic food, health, and nutrition services. The literacy rate is the lowest among all other communities. When I found out about them, I decided to work with them. In that connection, I was a regular visitor to such places to find ways to help these communities and bring them out of their existing situation. The person with a woolen cap and smiling face was one of the least educated boys from the village and had taken pain to help his villagers with health, nutrition, and increasing employment opportunities and income. The two other boys were curious to see what I am doing. Probably I had my mobile in my hand, which they were looking at.

How does this photo link to your field of expertise?

This picture could be linked with my work on health and nutrition and the right to food. However, my work was more focused on providing justice to the last section of people and communities—the ones who are most deprived. In my state, the PVTG community is one of them. They live in forests, mostly on hilltop, and reside in houses made of local thatched materials. Their source of livelihood is from the forest and hunting. Recently, they have turned slightly as farmers, doing some crops on the land available in between the forests. But, again, the literacy rate is very low. Hardly one will find a person that studied past 10th grades. Life expectancy is also very low. The average life expectancy is around 50 years. My work expertise perfectly matches with my social policy background and my pre IFP work on livelihoods. In addition, post fellowships work on public health added value to my expertise and the need of these communities. Truly speaking, my intensive work with them and with colleagues who supported my work with the PVTGs, especially Mr. Soumik Banerjee and Pragya Bajpeyee, for more than three years, have been instrumental in bringing few policy changes in favor of PVTGs and the Tribal population. These changes were on food security, health, and nutrition-related services in the state.

Do you see a link between this photo and your experience with IFP? If yes, could you tell us how this photo relates to your fellowship experience?

I conceptualized a broad understanding of the policy-related subjects more after I received the IFP fellowship I can count on my training and exposure, including the opportunity to pursue a higher degree at the London School of Economics (LSE). The course at LSE provided me an opportunity to understand the world, the policy-related issues, the governance system of the best-governed countries, and so on. At every step during the fellowship- starting from the preparatory training, language training, academic training at LSE, and the social justice training I gained-I could link once I was back to my country and community. The fellowship helped me understand the micro-macro linkages of issues and help develop strategies to overcome them both locally and at the larger level. I find that my international exposure helped much in helping the state government design the health program to support communities living in remote and hilly areas. Later, I got the opportunity to work at the state level on food security and social justice issues by holding a constitutional position under the National Food Security Act at my state as a member of the first-ever constituted State Food Commission since 2017. My commitment to work on social justice continues, and my focus on helping more than 75000 PVTG families across the state continues. I feel satisfied that my IFP fellowship helped me develop a broad vision and conceptualize the meaning of social justice in the true sense and spirit. In addition, my higher study provided me the tools of social justice.

Are there any concluding comments you would like to share?

Let the governments facilitate a system where it can help people lead their own lives by keeping their culture and heritage, language, livelihood opportunities intact; simultaneously, they can also enjoy the changing world and the opportunities available around. But, of course, it will require more work, more research and development, and finding ways of alternative or inclusive development approaches.

In this month’s edition, we highlight Basma Damiri from Palestine. Basma Damiri completed her IFP Fellowship in 2007 at the Clemson University in South Carolina, obtaining a master’s degree in Environmental Toxicology. Basma works as an Associate Professor in the School of Medicine and Health Sciences at An-Najah National University in Palestine.

Basma reflected on this photo of her and Sabrina, a young woman she has helped through her work and volunteerism.

After my graduation, I decided to help poor students who wish to complete their studies. Helping young students is the least I can do to pay it forward. God gave me a scholarship of tens of thousands of dollars. Otherwise, I would not have been able to finish my master’s degree or my Ph.D. If I help people all my life, I will not repay this amount. I feel that God has inspired me to help these people and pay it forward. I have a moral duty to help needy students. I love them well. I want to see them as I am now and better than me. I want them to hold higher degrees to serve their communities and alleviate poverty, injustice, and inequality imposed on marginalized groups. When I received my scholarship, I do believe that it was not by chance. It is because some people seek justice for others. It is like a snowball; the further it moves, the larger it becomes.

Today, I work in the School of Medicine and Health Sciences at An-Najah National University in Palestine. My beliefs prompt me to seek out those who need medical aid and treatment. I always search for vulnerable groups such as children, women, and refugees. Sabrina was a handicapped refugee child at that moment. She was born with a physical disability, and her leg was amputated due to a medical error. She lost her father when she was one year old and lost her leg when she was four years old. She lived in a poor house and could not complete her treatment. She dreamed of a wheelchair so she could go to school. Her dream was to have a scholarship that would cover her university studies. I wrote about her story on my Facebook page. Many followers interacted with the story. A donor donated a wheelchair to her, and An-Najah National University gave her a scholarship. She also got help to correct her amputated leg so that she can install a foot in the future. She is so gifted. Excellent public speaker and can sing so beautifully!

I just imagined myself when I saw Sabrina. I was too born with a disability. Because I want to pay it forward, I have the moral duty to help her make her dream true. Thank God that I was able to do that.

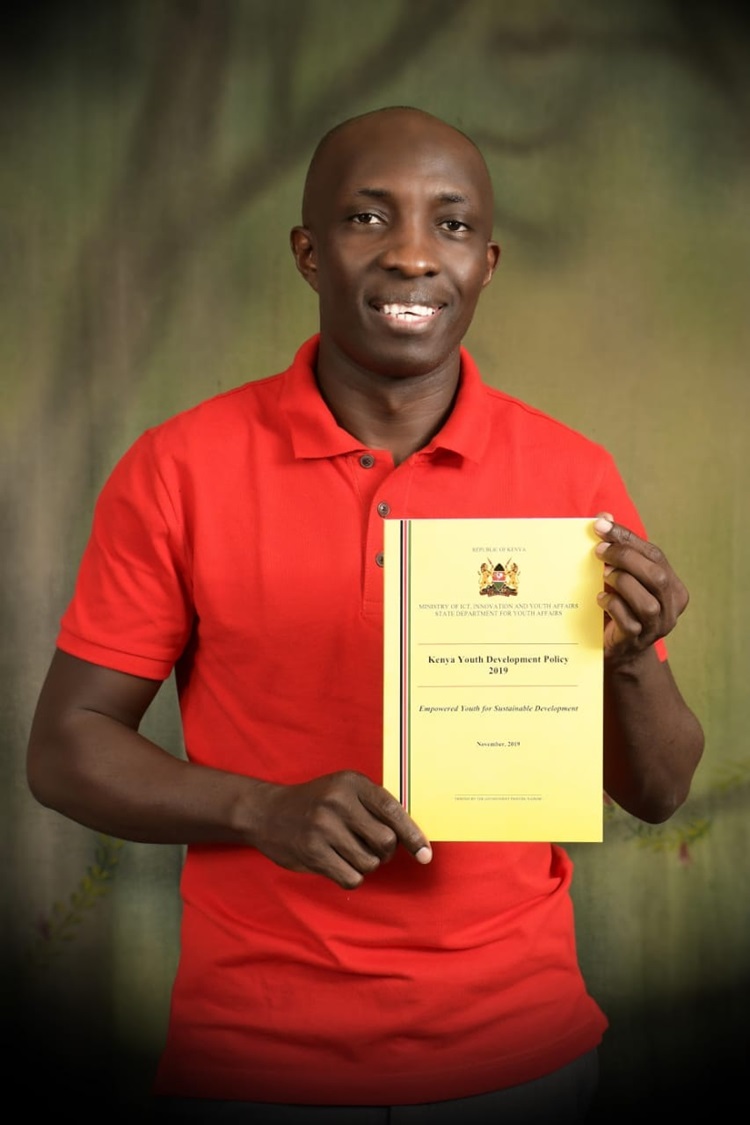

In celebration of World Youth Skills Day, July 15, we highlight Raphael Obonyo from Kenya in this month’s edition. Raphael Obonyo completed his IFP Fellowship in 2013 at Duke University in North Carolina, obtaining a master’s degree in Public Policy. Raphael works as a Public Policy Analyst in Kenya.

Can you describe these photos? When and where were they taken? It was the release of the Kenya Youth Development Policy in 2020. After five years of waiting, the country had finally birthed the Kenya Youth Development Policy setting off the long journey of its implementation to fully transform the lives of our young people for the generations to come.Having advocated for the policy and served on its Technical Committee, it is humbling and exciting to say that this document, if fully implemented, can be a game-changer for the welfare of the youth in my country.

How do these photos link to your field of expertise? I graduated with a Master of Public Policy in 2013 and returned to Kenya. While back in my country, I contributed to the five-year review of the National Youth Policy. I served as a Technical Youth Policy Reviewer.

Do you see a link between these photos and your experience with IFP? If yes, could you tell us how these photos relate to your fellowship experience? IFP emphasizes the need for connection between Academy and community, education, and social justice. Over the years, the lack of such an initiative denied the policymakers an opportunity to anchor the youth agenda in policy formulation, leading to many years of neglect and unfulfilled promises.The Kenya Youth Development Policy is an expression of the collective commitment of concerned stakeholders to harness and optimize the immense strength and opportunities that the youth in Kenya harbor, which they have failed to tap as they navigate both difficult personal and structural barriers curtailing their productivity.

Do you see a link between these photos and World Youth Skills Day? If yes, could you tell us how this photo relates to this celebration? Youth policy is essential for development. It provides a solid foundation for planning, interventions, resource mobilization, monitoring and evaluation, and reporting on youth empowerment and development interventions. The policy recognizes that youth development is not the responsibility of the government alone. It stipulates the obligations of other stakeholders, including state and non-state actors.

In celebration of the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, we highlight Svetlana Pantyukhina from Russia in this month’s edition. Svetlana Pantyukhina completed her IFP Fellowship in 2004 at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, obtaining a Master’s in Public Administration and Public Policy. Svetlana is an expert in rural tourism and the development of rural communities in Altai and wider Russia.

Can you describe this photo?

These photos were taken in the village Inya in the Altai Republic in Siberia, Russia, as part of the “School of Agrotourism and local crafts” project, sponsored by the Presidential Grants Foundation of Russia. I worked with local communities in the Altai Republic. I was a part of a team of experts, and we supported local people on how to start their rural tourism businesses. We have been working with several villages for over five years, and some families are now very successful. The project started in 2012, and I am still in touch with some families. I worked in many villages, almost every village in the Republic.

Could you share more about the local community?

The Altai Republic is an administrative division of Russia with a local population represented by Altaians. There are slightly less than 70,000 Altaians in the Republic, 34.5% of the Republic’s total population. Historically they are nomads breeding sheep and goats, also hunters. Few of them have had more or less traditional lifestyles until now. But some (surely those who live in the only city in the Republic) run businesses, work in offices, and have an ordinary life like many other people in other countries. Altai is one of the most popular destinations in the Russian domestic tourism market and, before the COVID-19 pandemic, also popular among international visitors who love to stay in the rural guest houses.

How does this photo link to your field of expertise?

It does relate to public governance partly. But my current specialization is narrower, and I am now one of the country’s leading experts in rural tourism. We consider it mainly an instrument for the development of rural communities and rural territories, and this is how it relates to public administration, my field of study. I have also been granted another scholarship, Chevening (UK), to deepen and improve my knowledge and professional qualification and dedicate myself fully to rural development via rural tourism.

Do you see a link between this photo and your experience with IFP? If yes, could you tell us how this photo relates to your fellowship experience?

Yes. My field of study sponsored by IFP was in public administration. Rural tourism and the development of rural territories relate to it directly, but I have a more specific subject now – rural tourism. However, we never see it only as tourism. It has a huge social component – and this is within governing the territories, which is part of public administration.

In this month’s edition, we highlight Dr. Sefakor Komabu-Pomeyie from Ghana. Sefakor completed her IFP Fellowship in 2013 at the School for International Training (SIT) in Vermont. She obtained a master’s degree in Sustainable Development and majored in Policy Analysis and Advocacy for Disability Rights. Sefakor earned her Ph.D. (2020) in Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at the University of Vermont. Sefakor works as the Independent Living Coordinator at the Vermont Center for Independent Living, Vermont.

Can you describe these two photos? These photos were taken during an empowerment workshop in Worawora, a town in the Oti Region of Ghana, last December 3rd, 2020. The workshop was part of a nationwide campaign project dabbed “The power of disability vote” sponsored by the Mobilizing Partners for Women, Peace, Security, and Strategy for Humanity. My NGO, Enlightening and Empowering People with Disabilities (EEPD AFRICA), trained and empowered over 50 people with disabilities for their rights to vote during the election on December 7th, 2020. They were also awarded a certificate of participation. We intentionally organized the workshop on December 3rd in fulfillment of Article 29 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability, which is about participating in political and public life on an equal basis with others and re-affirming the importance of their votes in support of development. December 3rd is the International Day of Persons with Disabilities.

Could you share more about the local community? Worawora is a town in the Biakoye District of the Volta Region, surrounded by the beautiful scenery of mountains. Kudje borders the town at the South, Asato Akan at the East, Apesokubi and the Volta Lake to the North, and Tapa Amanya to the West. Though settled in the Volta Region, the Woraworas speak Twi due to their ancestral origin from Kuntanase, near Lake Bosomtwe in Ashanti Region. The Worawora community’s principles and values are loyalty, rights, responsibility, and accountability. The town is also known for the Hospital and Secondary School, which is a second-cycle institution.

How do these photos link to your field of expertise? The photos link to my field of expertise because I have been working with people with disabilities worldwide, especially in Ghana, my home country. Both my master’s degree and Ph.D. revolved around disability policies and advocacy. As we all know, IFP’s focus is on fighting for social justice in all spheres of life. As a change agent and a person with a physical disability myself, I also vowed to connect my personal experiences with academic and professional works to fight for disability rights till the world becomes more inclusive and a better place for all people with disabilities. That was why the focus on the right to vote during last year’s election meant a lot to me.

Do you see a link between these photos and your experience with IFP? If yes, could you tell us how this photo relates to your fellowship experience? Indeed, the photos are directly connected to my experience with the IFP program. My field of study was a master’s degree in Sustainable Development, and I majored in Policy Analysis and Advocacy for Disability Rights. My Ph.D. was also in Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, where I dived more into different policies, especially educational policies, to align them with practices. Here is the real connection between policy and practices on the ground.

In this month’s edition, we highlight Margaret Kemigisa from Uganda. Margaret completed her IFP Fellowship in 2008 at the University of London, obtaining a Ph.D. in Public Health and Policy. Margaret works as a Team Leader at Rwengaju Irrigation Scheme in Kabarole District in the Western region of Uganda.

Can you describe the photos? When and where were they taken? Who are the community members in the first and second photos?

The photos were taken in the Karangura sub-county, Mount Rwenzori, around the River Mpanga, which feeds the Rwengaju Irrigation Scheme in Kabarole District. In August 2021, as part of the field activities to assess the river Mpanga, I met with some community members. Both the woman and man are from Karangura. The river is a source of livelihood for those in the business of stone quarrying, and also provides water for agricultural and other human uses. However, the stone quarry activity is a danger to the natural resource. It poses a risk to the community as riverbanks and areas adjacent to the riverbanks are excavated for their stones.

The woman you see me talking to in the first photo was explaining how the irrigation scheme has changed their lives while the man in the second photo was leading us to view the alternative livelihoods (bee keeping and coffee growing), having been displaced from the riverbanks where he was mining stones for a living.

The discussions are part of the initiative for various community interactions to generate locally based solutions to the challenges community members face to ensure they live in harmony with the environment. Eventually, the communities will develop bylaws to protect the river, adopt alternative economic activities, and work with the local leaders to address any emerging challenges.

How do the photos link to your field of expertise?

I wear different hats in my work with communities, sometimes as a researcher, sociologist, and public health specialist, among others. With a background in environmental and community health and public health and policy, I often find myself sensitizing communities and leaders to develop context-specific solutions to solving the development challenges that face them. For the last five years, I have worked on irrigation projects, leading teams of experts we develop and implement models to ensure sustainable farmer-based management of the irrigation schemes.

Do you see a link between these photos and your experience with IFP? If yes, could you tell us how these photos relate to your fellowship experience?

This work relates to social justice, especially since development projects should not displace communities without meaningful livelihood alternatives. As an IFP Fellow, there is always that inner voice that brings out social justice issues in work experience; some of these issues may be integrated into one’s mainstream responsibilities or generate different initiatives altogether that one may address independently. Within the Rwengaju Irrigation Scheme, we address other causes such as gender-related discrimination and power imbalances. I have supported the development of household economic planning tools that promote gender equality. These will eventually promote harmony and neutralize conflicts around resource utilization within households.

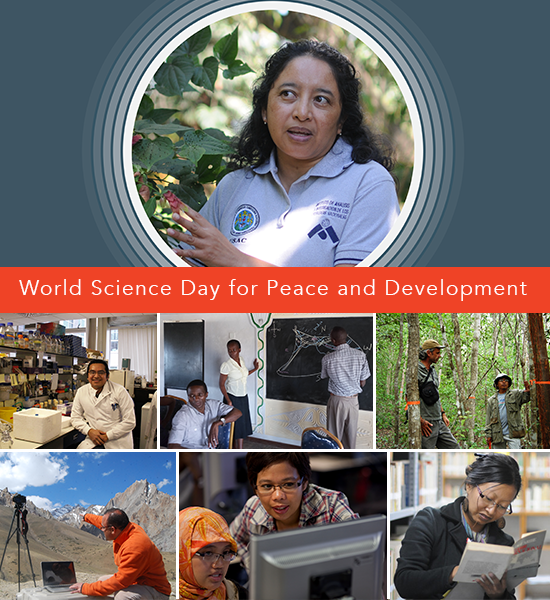

The Ford Foundation International Fellowships Program (IFP) supported individuals around the world in their education with the hopes of empowering socially committed individuals to advance change within their communities. Scholars were able to pursue whatever field to pursue this goal, and many chose science-based fields. One in five alumni (20%) pursued a field in environment, health, or applied sciences, and another 20 percent pursued a field in the social sciences. Alumni have since used scientific research, discovery, and advancement to support the communities in which they live.

Two such alumni were Aline Saraiva Okello and Alok Gupta. In Episode 1 of our Between Two Worlds podcast recorded in summer 2021, our IFP Study team spoke with IFP alumni pursuing careers in science fields outside their home country. Aline Saraiva Okello, a Water Resources Specialist from Tanzania now based in Kenya, spoke about her living in multiple countries and the reasons she continued to do her work abroad. Alok Gupta, an Environment Editor from India now based in China, spoke about his work studying how environmental policy affects rural communities and how such work was affected by media shifts in his home country. Aline and Alok were among the over 30 percent of IFP alumni who are pursuing work in environment issues, highlighted in our 2019 publication Leveraging Higher Education to Promote Social Justice: Evidence from the IFP Alumni Tracking Study.

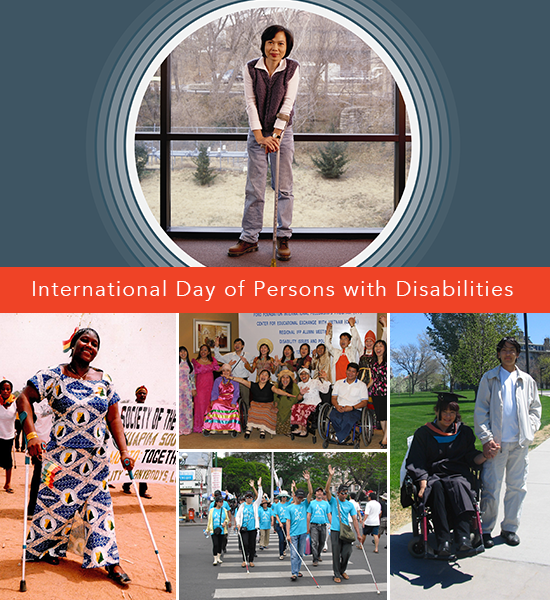

As part of its aim to provide higher education opportunities to disadvantaged groups from around the developing world, the Ford Foundation International Fellowships Program (IFP) provided graduate fellowships to nearly 175 emerging social justice leaders who have disabilities and/or work in areas of disability rights, advocacy, and service provision.

In our 2016 Issue Brief, “Disability is not Inability”, several alumni highlighted their experiences across many countries of origin. Abdul Busuulwa was a blind alumnus from Uganda who promotes disabled advocacy and mentors those with visual disabilities. Veronika E. Ivanova was an alumna from Russia and a wheelchair user who helped lay the groundwork for the Russian Disability Treaty. At the time of the Issue Brief, she was working as a translator and disability counsel for the Walt Disney Company.

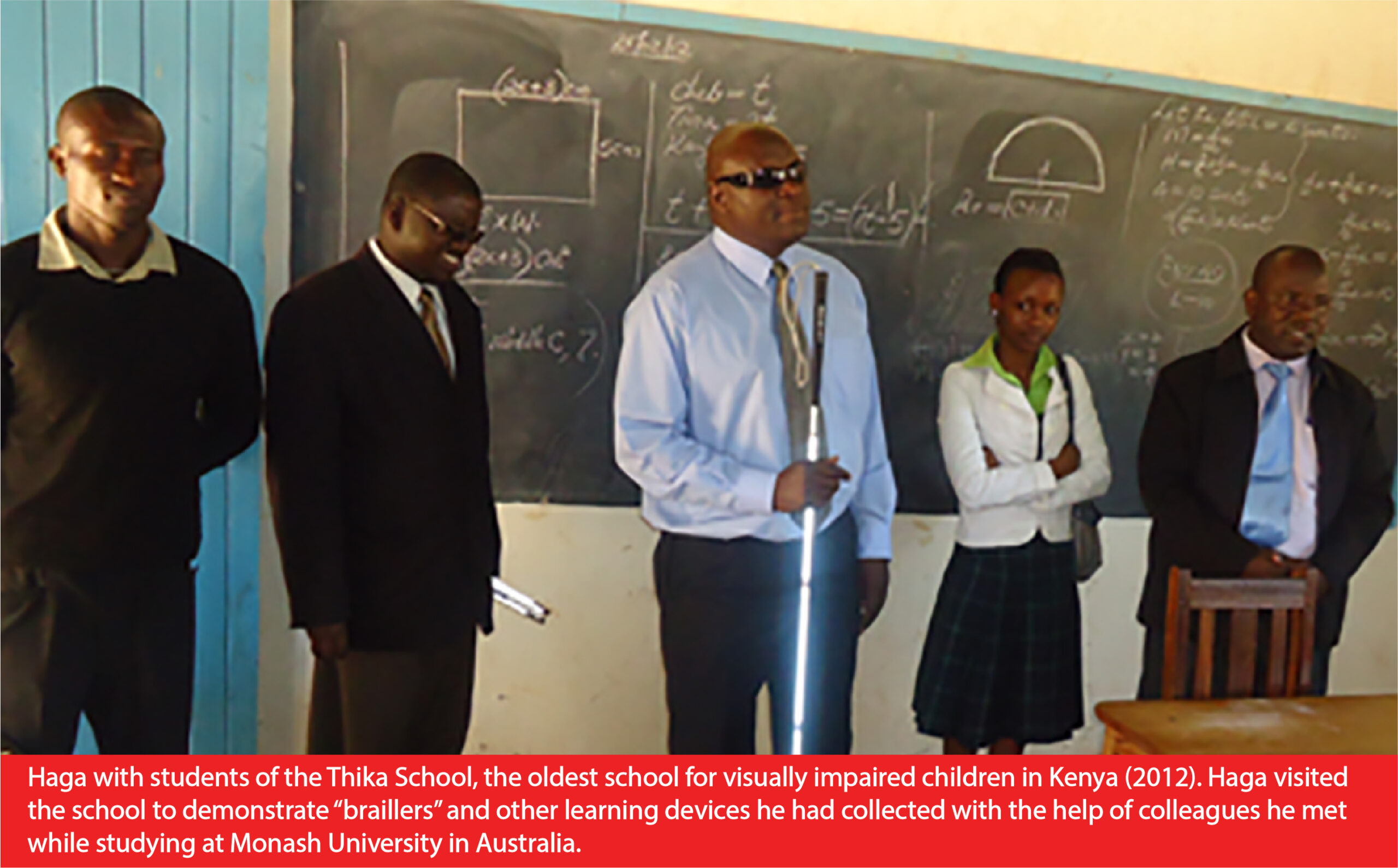

In an effort to bring about social change, The Ford Foundation International Fellowships Program (IFP) believed that promoting access to advanced education was key. The Fellowship supported graduate or postgraduate-level education for 4,305 emerging social justice leaders from 22 countries. Rather than following traditional selection criteria, IFP sought individuals from underserved communities that may not otherwise have had access to advanced education. Alumni studied in a variety of fields, and over 52 percent of IFP alumni were working in the education sector according to our 2019 publication Leveraging Higher Education to Promote Social Justice: Evidence from the IFP Alumni Tracking Study.

One such alumnus was Fred Haga from Kenya, pictured above. Fred lost his vision in high school, which forced him to drop out. Once he was able to pick up his education again, he was determined to improve the educational opportunities for disabled children in his country. Through IFP, Fred was able to complete his Master’s in Special Needs Education and take a position in the Ministry of Education, where he advocated for expanded co-curriculums, greater evaluation, and assistive technology .

Related Media: Fred Haga, Kenya & Alumni Stories and Impact

This month highlighted Ndeye Khady Mbaye from Senegal. Ndeye completed her IFP Fellowship at the University of Kansas, receiving a Master’s in Special Education and a Diploma in Curriculum Method and Assessment in Early Childhood Special Education. She now works as an advocate for children with disabilities.

Ndeye’s Story

When I was born, I had no congenital disabilities, and I received my disability at the age of four. According to my family, I was playing with an empty iron tomato paste pot when a neighbor boy strongly hit me in the back; I fell and became utterly unconscious. I was immediately taken to the closest medical center, where I was treated for my injuries. While I recovered, I was bedridden and could no longer stand. Every time my parents tried to help me stand up, I fell. Until nine, I could not walk, and I was crawling.

My parents were unsure what to do and did not consider enrolling a child with a disability in school. However, I believe education is the only thing that could make a difference in life.

The emotional pain caused by not having the opportunity to be provided with formal and quality education like my non-disabled peers was more significant than the physical pain caused by the disability itself. Using a pair of wooden crutches my parents had found for me, I would walk miles, sometimes under a hot sun, to go to the closest school and stay in the windows, to look at children my age read and write in their classrooms.

At the age of 12, I was accepted by one of my neighboring schools; I fought hard to overcome the many challenges, including the architectural barriers. When I received my secondary school diploma and went to the university, I started advocating for the education of children with disabilities. After receiving my Master’s in English, I volunteered at UNESCO’s Department of Inclusive Education to be closer to people with disabilities. The IFP Fellowship allowed me to study Special Education at the University of Kansas in the United States, where I obtained a Master’s in Special Education and a Diploma in Curriculum Method and Assessment in Early Childhood Special Education.

Could you describe the two photos?

In the first photo, To cultivate an inclusive, caring, and supportive environment for marginalized children with disabilities, we use the Nozomi Clinic test, a test like the Battelle Developmental Inventory (the BDI) for a child with a cognitive deficit. Here I am performing the screening. I will also test her fine motor, language, adaptive, and gross motor skills. After having the baseline, the child will need an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). I will give this child one-on-one instruction to give her a good head start.

In this picture, I am with two girls, Thiouba (on the right) and Rokhaya (on the left). Rokhaya has a physical disability, as does her mother, who is also in a wheelchair. Unfortunately, her mother did not have the opportunity to be enrolled in school. I did my best to find a placement for Rokhaya, now a sixth-grader. I urged them to work hard because education is the only thing that will help them make a difference. Here, we are discussing some concepts they learned in class.

This month, we highlighted Dr. Anupma Mishra from India. She completed her IFP Fellowship in 2010 at the University of Leicester, obtaining a Ph.D. in Education. She is working to improve the quality of education in rural areas of District Lakhimpur Kheri as a government teacher and a member of the State Resource Group in the Uttar Pradesh region, India.

Can you describe the photos? When and where were they taken?

Here I present some of my selected photos that reflect my recent work toward building equal social values and robust child development. The photos explore how we work with different schools, teachers, and teacher educators along with district-level officers to make school education more accessible and activity-based.

Could you share more about the local community?

My home district Lakhimpur Kheri is in the northern part of India, with 7,680 square kilometers. Most people live in rural areas. In 2011, the Kheri district had a population of 4,021,243—with a male population of 2,123,187 and a female population of 1,898,056. The male literacy rate was 69.57%, and the female literacy rate was 50.42%. The national government designated Lakhimpur Kheri as a Minority Concentrated District, requiring improved living standards and amenities. The district consists of a diversified group of people who often follow the traditional mode of living, with many Hindus; Muslims; Sikhs, and “Tharu.” Tharu are a tribal community who live at the Nepal border, and their daily practices are combined practices of Hindu and Nepali culture. There are strong caste values, and consequently, there are several socially deprived and economically disenfranchised families.

The position of girls in mainstream education is unsatisfactory because many girls are killed as feticides. Some mall practices against girls include child marriages , Dowry cases, domestic violence, and gender discrimination. Due to these firmly embedded social values, girl childbirth is considered a burden, and even if she receives an education and a job, females are not given equal respect in their families. However, this was not always the case among Tharu families (tribal families living in the district), which I learned when I took small-scale research about parents’ involvement in their children’s schooling after receiving funding through the 2018 IFP Alumni Awards .

Thus, there has been an urgent need to work with girls and mothers, enabling them to develop life skills and lead equal lives in society. I mainly work with deprived parents aiming to bring their children to the mainstream of formal education and develop life skills among them. Thus, I aim to motivate school-going children towards overall development through education by organizing various activities in and outside the school, enhancing their awareness of their legal rights and various social challenges, and involving parents and mothers in their children’s schooling for an improved society.

Do you see a link between these photos and your experience with IFP? If yes, could you tell us how these photos relate to your fellowship experience?

After receiving my IFP Fellowship, I had an opportunity to explore higher education in England. I enhanced my knowledge about various social issues and how to redirect them constructively. While working on my Ph.D. from the University of Leicester, I enhanced my understanding of schooling and parents’ support in educating their children. Thus, my efforts are maximizing children’s enrollment, regular attendance, involving parents, and training teachers to instruct girls constructively. I am trying to build a better community and society with literate people. Also, I am developing change-makers in the community to develop a society where everyone is equal and has opportunities to explore their personality as per their qualities.

Being an IFP Fellow brings a sense of responsibility to our society and nation. Thus, I am trying to contribute my best to society by sharing our knowledge and improving the lives of students and parents.